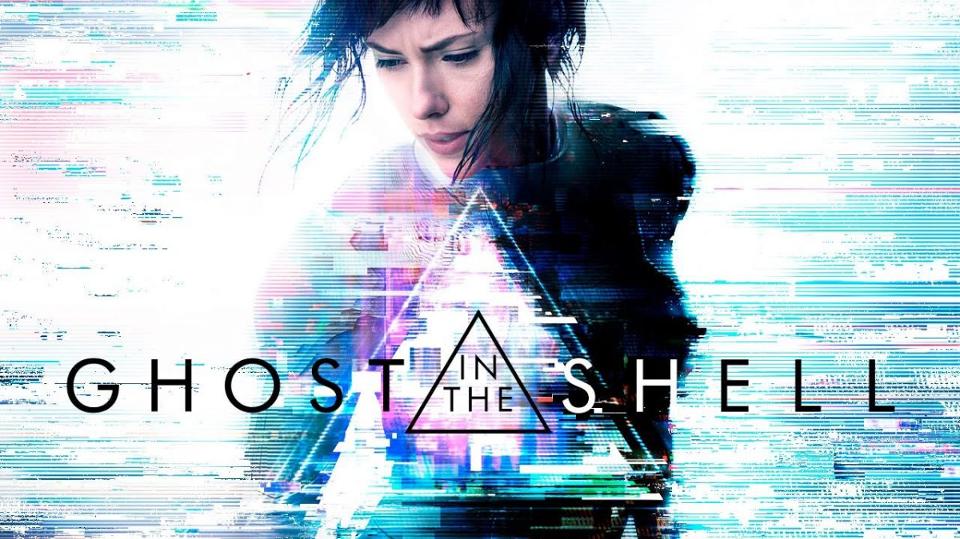

It’s been a month or so since the live action Ghost in the Shell movie starring Scarlett Johnson was released. I’ve read quite a few reviews and reactions so I already had a few questions before I set foot in the theater. I knew I had to see it myself to see how it all played out.

As an action film, it succeeds beautifully. As a meditation on technology and reality, it goes for soothing anxieties rather than exploiting them.

Let me explain.

[Warning: SPOLIERS!]

One the first things I noticed is how fast you buy into the idea that this movie is a Ghost in the Shell movie. The live action and CGI elements meld seamlessly together to create the world we all know and love. The first few scenes are familiar ones–Major standing atop a building, getting ready to kick some ass. The 2017 film uses the 1995 film much more as a basis than I had anticipated. It hits all the iconic scenes from the 1995 film (the invisible water fight, the boat scene, the spider tank fight) and there’s a search for an elusive terrorist. The villain Kuze is similar to the Puppet Master, but puts a unique spin on who exactly this “terrorist” is. The big departure is how the 2017 movie integrates Major’s origin story into the plot.

One of the major questions I had going into this film was why anyone would put a ghost into a white woman that is meant to work for the Japanese police. I’ve existed as a white women in Japan and let me tell you, you stick out like a sore thumb. The movie does answer that question somewhat, although it’s probably unintentional. All the people who work the cybernetics corporation Hanka–Mr. Cutter, Dr. Oulet, and more–are white. You might infer that Hanka considers white ethnicity as default.

Despite the whiteness of Hanka, members of Section 9 are diverse–they are black, white, and asian. There are American accents and British accents. Togusa is played by a Chinese actor and speaks English with a British accent. The sanitation employees are white men who speak non-accented English. Hanka meets representative from the African Federation and Major meets a black woman. Chinese and Japanese script appears on signs and advertisements, but it isn’t strikingly different than what you would see in, say, Chinatown in New York City. The only critique I would have is that, after coming back from a recent trip to China, white people appear in advertisements in Asia much more than you would think. (Who’s exotic now?)

Despite the diversity of the cast, Aramaki, the head of Section 9, is the only character who speaks Japanese in the film. There have been several reviews–even Japanese ones–that mention this as a huge drawback. I thought this was an odd thing to say. In the future with cybernetics, why wouldn’t everyone have a translator attached to their brain? After seeing it in action, I can see how it could be completely jarring. The audience literally has to switch from listening to reading from sentence to sentence.

However, one interesting implication from this choice was that it centers Aramaki as Japanese in the film. Aramaki repeatedly tells the people at Hanka that he does not answer to them, but rather the Prime Minister. Which left me with the question–the Prime Minister of where? I was left with the impression that if New Port City is a Japanese city of the far future, this future looks more similar to the one in Attack on Titan. Of course, Aramaki is not the only Japanese character in the film as we are led to believe.

Before Dr. Oulet bites the big one, she gives Major the address to place where she will find her memories. Major goes and meets an older Japanese woman who tells her about her missing daughter, Motoko Kusanagi. When Major confronts Kuze, she finally remembers her past: Major and Kuze are Motoko and Hideo who were exploited for Hanka’s own ends. Some activists have noted that this takes a unique place in Hollywood whitewashing–it’s whitewashing and yellow face at the same time.

As an anime fan who has seen the Japanese origins scrubbed from Japanese properties (See: The DIC adaption of Sailor Moon), I appreciate the effort to include the original material, but it doesn’t take the same care with Major’s ethnicity. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo takes place in Sweden and gets the ethnicity of the characters correct. Ultimately, Major could have been played by an Asian American actress with the same exact script. Audiences would then have to accept the name Mira Killian–which seemingly wouldn’t be too hard to do since we are asked to do same with Emma Stone’s character in Aloha. In my review of the 1995 film, I wondered how an American actress for Major could question identity. The 2017 film tries to sooth any anxieties regarding technology and globalization that the 1995 film suggested. In the 2017 film, a Japanese identity is found again underneath all the western cybernetic parts.

So while Ghost in the Shell (2017) succeeds as an action film and a stunning visual extravanganza, as a philosophical sci-fi film, it contradicts itself. In the film, we see characters with cybernetic parts get hacked, go haywire and memories manipulated. However, the message at the end of the film is that memories don’t matter. When Major learns of her past, we learn that Motoko Kusanagi was an anti-technological anarchist–a far cry from the fully cyborg, government employee she is today. Major leaves the audience with the parting thought that memories do not define you, but what you do does. It seems Major ceases to care about her past despite it being the driving force throughout the whole movie.

So, what is Ghost in the Shell‘s place in Hollywood’s anime adaptions? Hollywood proves that it can make a stunning live action adaption. However, Hollywood still hasn’t come to grips with the place of Asian American actors. If Hollywood wants to continue to adapt anime, they will need to face it–and they better start now.