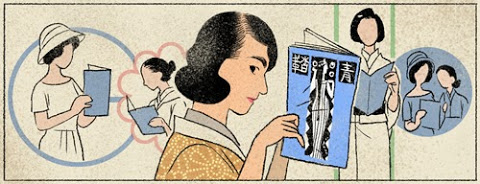

On February 10th, 2014, the above Google Doodle created by Katy Wu graced the Google landing page. Google has been criticized in the past for heavily featuring white men. From 2010 to 2013, only 17.5% of these doodles were women. My interest was peaked.

The woman in the center of the image is Raichō Hiratsuka, feminist writer and activist, who co-founded the literary magazine Seitō (meaning Bluestocking). In 1920, she founded the New Women’s Association and speared headed the first attempt to win women’s right to vote in Japan. Previously, I’ve written about Beate Sirota Gordon, the young woman who wrote women’s suffrage into the new Japanese constitution in 1945. But who was Raichō Hiratsuka? What was the state of women’s rights in Japan before 1945? I had no idea. Luckily, I was able to find an English translation of part of her autobiography called In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun.

I was not disappointed.

Raichō begins her autobiography with a scene of a parade. Her three year old self observes the festivities, perched on her grandmother’s back. The date was February 11th, 1889, the day which the Meiji Constitution was formally declared. Social change, it seems, was something that Raichō was literally born into. Her father was a high ranking government official; he was fluent in German and wrote some sections of the new constitution.

One of the great joys of reading her autobiography is the sheer beauty in which she describes Meiji-era Japan. She writes of a simpler time. It’s almost like reading a passage from Little House on the Prairie:

The straw snakes and roasted barley cakes were the biggest attractions at the Fuji Shrine. The snakes were supposed to ward off diseases and evil spirits, but I preferred the cakes, which came in sturdy paper bags with twisted paper handles and a picture of Mount Fuji in blue on the side. Just thinking about them now, I can almost smell the aroma of roasted barley. (page 34)

I was eager to learn what inspired Raichō to become a feminist. From an early age her mother made her very aware of the differences between boys and girls–boys could catch cicadas, but girls couldn’t. Her mother obsessed over Raichō’s appearance–applying a thick, sticky liquid to straighten her fizzy hair.

She had done this ever since I started to wear my hair in bangs, and I simply hated it. ‘That’s enough, that’s enough,’ I would say, but no matter how much I protested, she refused to give in. My father and grandmother had wavy hair, but no one seemed to care about them; it was unfair. (page 33)

Like many feminists, Raichō recalls how her mother and grandmother wished she were a boy; Raichō was simply not beautiful, her wide features and dark skin were not at all feminine. Her sister, however, was growing more and more “ladylike.” In high school, Raichō surrounded herself with like-minded friends. They dreamed of jobs and independence instead of motherhood and family. (page 45)

I don’t know about you, but I’d definitely have a beer with Raicho. Credit: Wikipedia

However, it was her interest in religion and philosophy that propelled her forward. After attending a lecture on Buddhism in high school, Raichō decided to study further at the newly opened Japan Women’s College. To her surprise, her father was against the idea–that too much education made women “unhappy” and that his parental duty ended at high school. Luckily Raichō’s mother interceded, and she was allowed to enter as long as she majored in home economics. Raichō entered the college in 1903 at the age of 17.

Japan Women’s College was founded by Naruse Jinzō, an ordained Christian minister who had study theology in the United States. His passion for philosophy, ethics and women’s education invigorated Raichō. She became a voracious reader, reading anything that might lead her to answer the questions, “What is God? What am I? What is truth? How should one live?” (page 76) Raichō went to a Christian church, but she felt the sermons did not quite answer her questions. She was on a path of understanding, not of faith.

Then, by chance, Raichō happened upon a classmate’s book on Zen Buddhism. She was floored by what she read: “Seek the Great Way within yourself. Do not seek it outside yourself. The wondrous force that wells up within you is none other than the Great Way itself.”(page 83) At the temple, Raichō was immediately assigned her first kōan and instructed to meditate on it. Raichō had finally found what she was looking for.

After graduating college in 1906, Raichō continued her studies, but this time, she would study English. She read and translated passages from English novels and poems. She participated in literary societies and it was during this time she became enthralled with one of the lecturers, Morita Sōhei. Despite being married, he returned her feelings. Raichō was not interested in a sexual relationship. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, she was interested in living her life freely. Morita, on the other hand, became more impassioned. He was determined to end their love affair in the most dramatic way possible–with a “romantic” murder-suicide in the mountains. Raichō says she doesn’t believe him, but indulges in his fantasy anyway. Her suspicions are correct and Morita becomes a weak, crying mess on the side of the mountain, unable to follow through with his plans. Raichō stays cool, calm and collected until a policeman finds them the next day.

At the end of this story, I thought Raichō would launch into a long rebuke of Morita, but she doesn’t. She wishes him and well and hopes the novel he writes of this event–an event that would tarnish her reputation in the newspapers–is well written. This passage reminded me of a Jane Austen novel–lengthy descriptions that don’t make sense until the very end when you realize what just really happened. Whatever polite society may have thought of this “scandal,” Raichō conveys to her readers she came out on top. Morita–the man–was the weak, emotional one.

If society didn’t acknowledge Raichō’s strength and independence, Raichō’s friend Chōkō certainly did. He urged her to use this strength to help humankind rather than her own self. He convinced her to start a women’s literary magazine. That literary magazine was Seitō.

The cover of the first issue of Seito. Credit: Wikipedia

Up until this point in her autobiography, Raichō downplays her interest in literature and women’s issues. So when Raichō shares her opening essay in the inaugural issue of Seitō, it’s almost shocking. Here are my favorite passages:

In the beginning, woman was truly the sun. An authentic person. Now she is the moon, a wan and sickly moon, dependent on another, reflecting another’s brilliance.

Seitō herewith announces its birth.

Created by the brains and hands of Japanese women today, it raises its cry like a newborn child.

Today, whatever a woman does invites scornful laughter.

I know full well what lurks behind this scornful laughter.

Yet I do not fear in the least…Is woman so worthless that she only brings on nausea?

No! An authentic person is not…

In the beginning, woman was truly the sun. An authentic person. Now, she is the moon, a wan and sickly moon, dependent on another, reflecting another’s brilliance.

The time has come to recapture the sun hidden within us. “Reveal the sun hidden within us, reveal the genius hidden within us!” This is the cry we unceasingly cry out to ourselves, the thirst that refuses to be suppressed or quenched, the one instinct that unifies all and sundry instincts and ultimately makes us a complete person…

Our savior is the genius within us. We no longer seek our savior in temples or churches, in the Buddha or God.

We no longer wait for divine revelation. By our own efforts, we shall lay bare the secrets of nature within us. We shall be our own divine revelation…

…Woman will no longer be the moon. On that day, she will be the sun as she was in the beginning. An authentic person.

Together, we shall build a domed palace of dazzling gold atop the crystal mountain in the east of that land where the sun rises. Women! When you draw your likeness, do not forget to draw this golden dome…(page 157 – 159)

This essay is one of my all-time favorite feminist manifestos. And as a blogger who blogs about a superhero who represents the moon, I can’t ignore this irony. Over 100 years after Raichō wrote these words, the most popular heroine from Japan is an avatar of the moon, not the sun. Perhaps the moon isn’t so weak and sickly now, no?

The last panel of the Sailor Moon manga proclaims Sailor Moon is the most brilliant star for all eternity. Her light is even more brilliant than the sun.

Credit: missdream.org

In the Kodansha English translation, the word “hoshi” is translated “heavenly body,” making Sailor Moon the brightest of all heavenly bodies in the sky. Screw the sun, we’re overtaking supernovas, guys! This begs the question—could Takeuchi-sensei be making a reference to Raichō’s essay? If so, the title Moon Pride suddenly makes much more sense. The concept of “shining” seems to be a well-known symbol of women’s empowerment in Japan, for better or for worse. Shiny Make Up, indeed!

But that’s not the only manga reference.

The final panel of the third arc, Sailor Moon SuperS, a lone Usagi, clad in her new high school uniform, looks up at the sun.

Credit: missdream.org

As she looks at the shining sun, she thinks to herself:

“I must fight to protect all those people who are important to me so I can make my dreams come true. I beg you star in my heart, please keep shining. Give me strength!”

With this shining strength, she can be true to herself and pursue her dreams. The moon has become as bright as the sun, and this time, shining with her own light.

Finally, I can’t be the only person who thought of Crystal Tokyo when Raichō declares, “Together, we shall build a domed palace of dazzling gold atop the crystal mountain in the east of that land where the sun rises.” It’s not just a crystal mountain–it’s a whole darn prefecture! And ruled by the most powerful form of Usagi, Neo Queen Serenity.

Credit: silver moon tumblr

Seitō only lasted five years, until February 1916, but it galvanized the women’s movement. This would just be the beginning of Raichō’s activism. The translator, Teruko Craig, includes an afterword detailing these events. She covers a lot of ground within thirty pages, and it’s a shame, because this era of Raichō’s life is fascinating.

After seeing the horrible working conditions women suffered in textile mills, Raichō fought for women’s suffrage. Unfortunately, Raichō’s efforts failed and women’s suffrage was voted down. One opponent of the bill, Baron Fujimura Yoshiro, declared women participating in politics were against the laws of nature and used Taira Masako, Empress Wu and Queen Elizabeth as proof that women with political power do no good (page 300). It was March 26th, 1921.

Devastated by this setback, Raichō retreated from public life. When Japanese women finally earned the right to vote in 1945, Raichō reacted to the news with relief, but also anger. It shouldn’t have taken a war and a foreign country to deliver those rights (pages 312-313).

Raichō passed away in 1971 at the age 85, leaving behind an impressive legacy. I thought I would be unable to relate to her story, but I was completely wrong. Thanks to Teruko Craig’s amazing translation, you feel like Raichō is sitting right next to you, telling her story. Raichō’s words cross space and time like the light of the sun, providing warmth and life.

Note: I was unable to cover all aspects of Raicho Hiratsuka’s life in this post. Please feel free to share any additional information, positive or negative, in the comments below.

What a wonderful read! Thank you for sharing parts of this amazing woman’s life with us! I always been interested about feminism in Japan, and now I’m definitely getting this book someday. Very nice parallels with Sailor Moon here too!

Thanks! I think people know about Japan’s regressive attitudes towards women, but less so about it’s own history of fighting for women’s rights. Women’s rights aren’t just some weird, small thing–it’s a worldwide movement, and it’s been that way for a long time.

Its kinda ironic that he used queen Elisabeth as an example of why a woman shouldn’t be allowed to be politicians as she was (in her prim) one of Britons most stable and strong rulers. Defenetly the best monarch to come out of the Tudor dynasty

I know, right? Seems a little xenophobic to me too.

Oh! And I forgot to add–at the recent Sailor Moon Vivi event, male attendees had to be escorted by a female friend. Seito held a public lecture back in 1913 or so, and they did the same thing to prevent male hecklers. I thought that was really interesting!

I’m doing the paper about Raicho’s book, in the beginning woman is the sun.

Thank you for your deep and interesting explanation and parallels with Sailor moon is really unique perspective and connection.

Do you think women should turn back the position when they were sun in the beginning or like Usagi shined her strength made moon as shining as sun?

I think it still slightly different between being sun or moon to some degree.

Somehow I feel like being moon is the a compromise. Even a alternative of being sun. Even if moon is as bright as sun.

Wow that’s so cool!

Oh, that’s a difficult question. I love moon goddesses–Diana, Artemis (ehehe, and Sailor Moon!). So I don’t want to give up moon goddesses, but I do love the idea of returning to the Sun Goddess idea. There are so many male sun gods (Ra, Apollo etc.), that I want to think how our perspective would change if we considered a female sun goddess. But I think regardless, it’s most important that women have the right to self-determination and that we honor women’s skills and strengths. In that way, it’s doesn’t matter if we are Moon Goddesses or Sun Goddesses–we are the goddess of all things! (Maybe like Sailor Cosmos? LOL)

Thanks for your reply!

Really like the last part you said- we are the goddess of all things!

Just trace back to the fundamental right to human not referred to any gender. (still need time to realize this thou

BTW,recently Sailor moon became another fever choice as Halloween cosplay.

Even my male friend dressed up as Sailor Mars I guess

I saw Halloween pictures from Japan on twitter! I’m so happy to see all the Sailor Senshi!

Hi, I’m trying write a dissertation about the Seitô magazine. But i am from Brazil and it is has been a real challenge. Maybe can you indicate where i can find it? or maybe lend me somehow. I will be really grateful. And i love your insight about moon isn’t so weak. And finally, thank you for writing something about Raicho Hiratsuka and Seitô she deserves be

recognized.

Thank you! I think there are some books in Japanese. Maybe you can find something on Amazon.com? Or even Amazon.jp?

If you click on the links in the article, they’ll take you to the Amazon page for the book I referenced.

Good luck on your dissertation!